Americans' reliance on household debt ─ and poor people's struggles to pay it off ─ has fueled a collection industry that forces many of them into jail, a practice that critics call a misuse of the criminal justice system.

The accusation is documented in a report by The American Civil Liberties Union, which spent more than a year investigating collection methods across the country, saying it found more than 1,000 cases in 26 states in which judges, acting on the request of a collection company, issued arrest warrants for people they claimed owed money for ordinary debts, such as student loans, medical expenses, unpaid rent and utility bills.

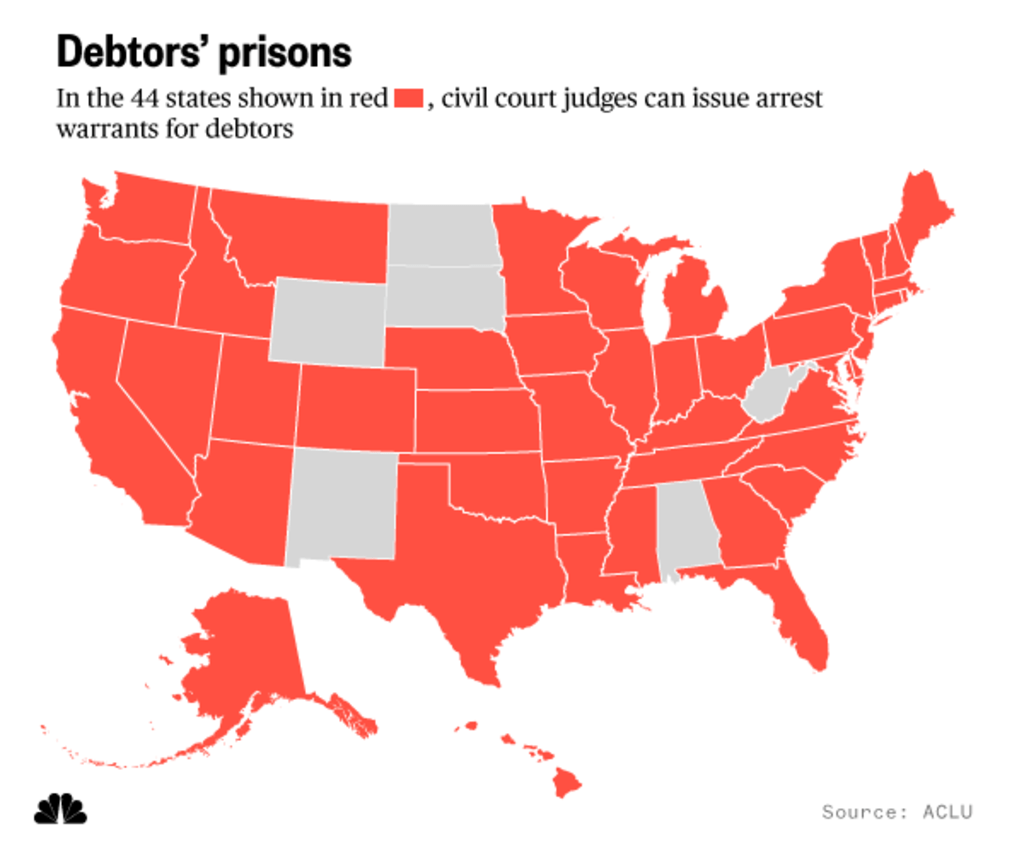

The results ─ just a glimpse of a phenomenon that spans at least 44 states ─ are further evidence of a justice system that criminalizes poverty, from cash bail to the jailing of people over unpaid court fines to the use of private probation companies, the ACLU said.

This is how it works, according to the report:

- Someone falls behind on a bill, and the outstanding payment gets sent to a collection agency. The agency takes the debtor to small-claims court. Most debtors don't defend themselves, either by choice or because they never learn of the lawsuit.

- The court, overwhelmed with such claims, rules for the collection agency, which then asks a judge to hold a hearing in which the debtor must answer questions about his or her ability to pay. If the debtor doesn't show up — and they often don't even know about the hearing — the agency asks the judge to issue a civil warrant for the debtor's arrest. This warrant doesn't technically cover the money owed, but the failure to appear in court.

- These warrants can appear on someone's record, making them subject to arrest if they are targeted in a warrant sweep, are stopped for a traffic violation or go to authorities to report a crime they witnessed, according to Jennifer Turner, the ACLU's principal human rights researcher and author of the report. Often they are issued bail in the same amount as the money they owe.

"They are never charged criminally, and the warrants are still civil, but they still lose their liberty," Turner said in an interview. "They don't have a criminal record, but they suffer a lot of the same collateral consequences."

Turner collected examples of people ending up in jail in this manner. The cases, as described in her report, include an elderly Maryland couple who owed $2,300 to their homeowner's association; a Minnesota man placed in solitary confinement on an auto insurance debt despite the fact he'd filed for bankruptcy protection; a Georgia mother whose former landlord said she owed back rent; and an Indiana cancer survivor who'd fallen behind on her treatment bills.

The states with the most egregious abuses, Turner said, were Maryland ─ where President Donald Trump's son-in-law, Jared Kushner, reportedly sought the arrest of tenants of his real estate company ─ and Massachusetts, which are both considering legislation to curb such arrest warrants. The model, she said, was Illinois, which ended the practice in 2012.

The ACLU is going to push more states to change their laws, and file lawsuits to force change, Turner said.

This effort is part of a larger movement among civil rights groups and advocates for criminal justice reform to curb practices they say discriminate against the poor.

That includes targeting what they call "modern-day debtors' prisons."

A wave of investigations and lawsuits by civil rights organizations is forcing local courts to curtail their reliance on fines, fees and surcharges related to traffic tickets and other minor offenses. And state and local officials are finding ways to allow indigent people to avoid falling into a cycle of debt and incarceration

No comments:

Post a Comment