In some parts of the country, the economy is so strong that companies can’t find enough workers to fill all the orders they have. Yet wage growth is weak, participation in the labor force is low and some areas seem chronically depressed. And economists can’t quite explain these disparities.

New research by the Conference Board examines one factor that might account for the large number of workers on the sidelines: disability. The portion of working-age adults who say they’re not in the labor force because of a disability rose from 4.2% in 1995 to 6.1% in 2017, according to government data analyzed by the Conference Board. The unemployment rate was 5.6% at the end of 1995, and it’s much lower now, at 4.1%. So you’d think the economy is stronger now. Yet GDP growth is actually lower now than it was in 1995.

Today’s higher disability rates suggest there’s more softness in the labor market than the low unemployment rate suggests. “There’s no doubt there’s a connection between labor market conditions and the share of people saying they’re disabled,” Gad Levanon, chief economist at the Conference Board, told Yahoo Finance. “The disability rate reflects weak labor market conditions in some areas.”

Getting in the way of growth

And that, in turn, may frustrate President Trump’s goal of sharply boosting economic growth. Trump insists his policies will help the economy grow at sustained growth rates of 3% or more, compared with the 2.2% average of the last five years. But cutting taxes and easing regulations won’t do the trick, if companies are turning down business because they can’t find enough workers, and several million people who ought to be earning and spending money instead are relying on others.

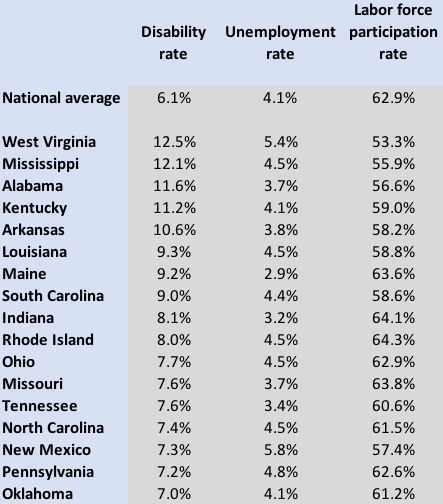

The Conference Board, as part of a new report on labor shortages in the economy, broke down disability rates by states for adults aged 20 to 64. In 17 states the disability rate is 7% or higher, and it’s above 10% in five states: West Virginia, Mississippi, Alabama, Kentucky and Arkansas. Here’s the national map:

One important caveat: These disability rates are not the ones used to determine who gets federal disability benefits under the Social Security program. That’s a completely different system. So these numbers don’t represent people saying they’re disabled just to get a government check. Rather, these are answers to Census Bureau survey questions asking people why they’re not in the labor force.

People who say they’re out of the labor force on account of disability aren’t counted in the unemployment statistics, which only measure people who have a job or are looking for a job. The 13.8% of working-age adults in West Virginia who are out of the labor force because of a disability, for instance, don’t have a job, aren’t looking for a job, and aren’t counted as unemployed.

Weak participation

But it’s those people who are completely out of the labor force who may explain labor shortages, sluggish economic growth and living standards that have barely been rising. While the unemployment rate is close to record lows, the portion of Americans who have a job or want one is also low. The so-called labor force participation rate peaked at 67.3% in 2000. It’s now at just 62.9%, roughly equal to where it was in the late 1970s—before women began surging into the work force. Disability may be one of the reasons the participation rate is so weak.

Six of the seven states with the highest disability rates have participation rates well below the national average. Here are the numbers for all states with a disability rate of 7% or higher:

So it could be a high rate of disability in some states that is hollowing out the work force, or at least contributing to a hollowing out. Normally, when the economy improves and employers create more jobs, pay goes up and that draws some people off the sidelines—even people who consider themselves disabled. That has happened somewhat in the current recovery, which has been underway since 2009. But the trend this time has been muted, with more people staying out of the work force for longer. Economists can’t fully explain that, but in addition to disability, it may involve opioid addiction, lack of relevant skills in a fast-changing digital economy, and government benefits that create a disincentive to work.

States with high disability rates don’t necessarily have high unemployment rates. In fact, three of the seven states with the highest disability rates have unemployment rates below the national average. But the high disability rate means those states also have a significant portion of working-age adults who might have been in the labor force 20 years ago, but aren’t now.

For employers, this may help explain why workers are hard to find, even when pay goes up, as Yahoo Finance documented in a February report. Labor shortages could become more acute in coming years, and they may already be constraining growth, because there are fewer people earning money and generating economic activity. For President Trump, it means tax cuts and deregulation may not be enough to hit 3% growth rates. He may also have to persuade people who aren’t working that they should get off the sidelines.

No comments:

Post a Comment