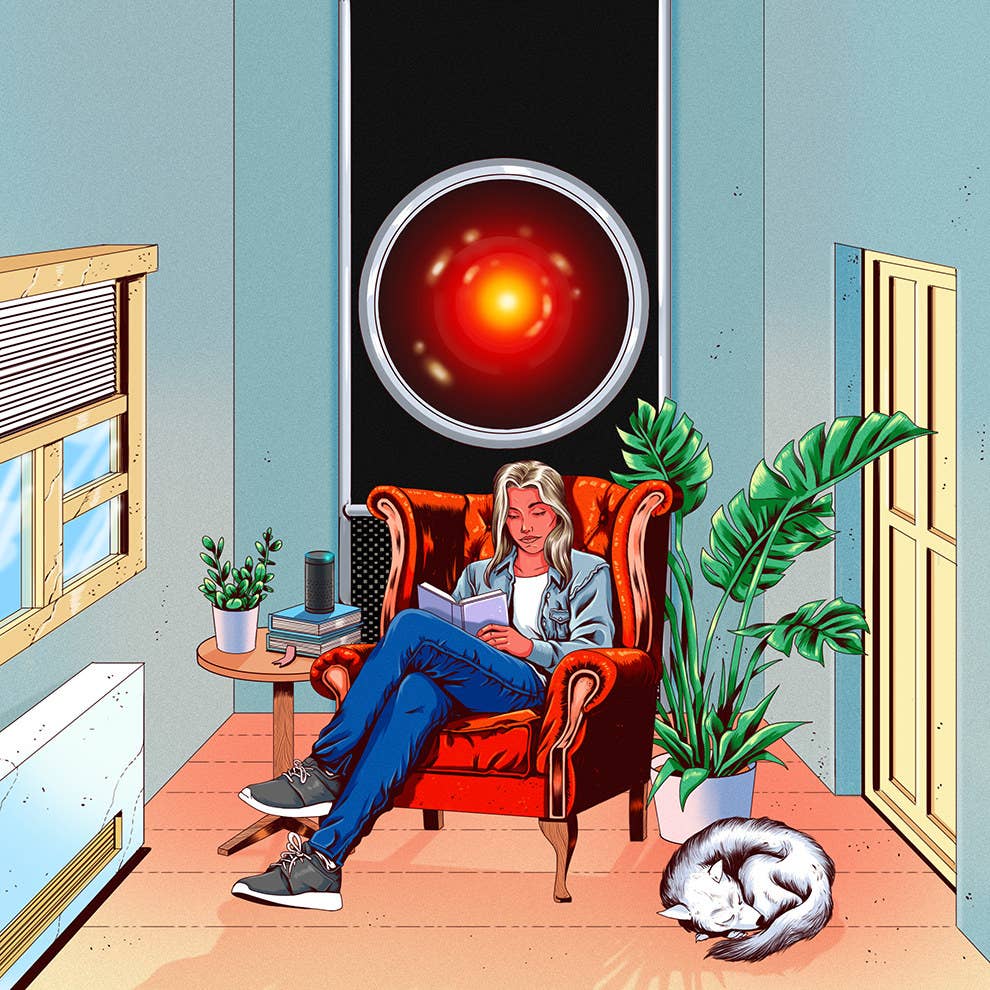

In 1964, director Stanley Kubrick, fresh from the success of Dr. Strangelove and not yet quite 36, set out to make what he hoped would be “the proverbial ‘really good’ science fiction movie.” What has endured in the annals of popular culture since then — even for those who aren’t familiar with his resulting 1968 masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey — is the talking computer named HAL, which quietly murders most of the human crew under its care. When the astronaut-protagonist Dave Bowman, played by Keir Dullea, asks HAL to open the pod bay doors to let him back into the spacecraft, it refuses, instead intoning the now-infamous phrase, “I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

In 2018, HAL has real-life analogs that don’t defy or destroy its human interlocutors. They are the voice-controlled, AI-powered digital assistants from tech heavyweights Google, Amazon, and Apple, inspired by speculative fiction and made feasible by the technological shifts that have occurred in the five decades since 2001: A Space Odyssey premiered. These shifts include the invention of the internet, dramatic gains in computational power at diminishing cost, and the relatively recent renaissance of artificial intelligence research following periods of “AI winter” in the 1970s and 80s when the field fell into disrepute and defunding. Now, the computer systems that power voice assistants — systems distributed across server farms around the world and only partly residing on our personal devices — are capable of learning through algorithms designed to mimic human neural networks, accurately recognizing what we say and generating natural-sounding speech in response. Just today, Google previewed an experimental version of the Google Assistant with a feature called Google Duplex, which allows the assistant to call a specific business like a restaurant or a hair salon and make an appointment, talking naturally — with hesitation and vocal fillers to boot.

And so it seems a little like kismet that in these early months of 2018 — months leading up to this spring’s 50th-anniversary theatrical rerelease of 2001: A Space Odyssey — Google, Amazon, and Apple have each unleashed big-budget ad campaigns for their respective voice assistants. The object of these commercials is presumably to convince non-users, amounting to slightly over half of Americans, of the myriad ways in which the peppy, by-default female-voiced Google Assistant, Alexa, and Siri might each make modern living a little less anarchic, and a little less stressful.In 1964, director Stanley Kubrick, fresh from the success of Dr. Strangelove and not yet quite 36, set out to make what he hoped would be “the proverbial ‘really good’ science fiction movie.” What has endured in the annals of popular culture since then — even for those who aren’t familiar with his resulting 1968 masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey — is the talking computer named HAL, which quietly murders most of the human crew under its care. When the astronaut-protagonist Dave Bowman, played by Keir Dullea, asks HAL to open the pod bay doors to let him back into the spacecraft, it refuses, instead intoning the now-infamous phrase, “I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

In 2018, HAL has real-life analogs that don’t defy or destroy its human interlocutors. They are the voice-controlled, AI-powered digital assistants from tech heavyweights Google, Amazon, and Apple, inspired by speculative fiction and made feasible by the technological shifts that have occurred in the five decades since 2001: A Space Odyssey premiered. These shifts include the invention of the internet, dramatic gains in computational power at diminishing cost, and the relatively recent renaissance of artificial intelligence research following periods of “AI winter” in the 1970s and 80s when the field fell into disrepute and defunding. Now, the computer systems that power voice assistants — systems distributed across server farms around the world and only partly residing on our personal devices — are capable of learning through algorithms designed to mimic human neural networks, accurately recognizing what we say and generating natural-sounding speech in response. Just today, Google previewed an experimental version of the Google Assistant with a feature called Google Duplex, which allows the assistant to call a specific business like a restaurant or a hair salon and make an appointment, talking naturally — with hesitation and vocal fillers to boot.

And so it seems a little like kismet that in these early months of 2018 — months leading up to this spring’s 50th-anniversary theatrical rerelease of 2001: A Space Odyssey — Google, Amazon, and Apple have each unleashed big-budget ad campaigns for their respective voice assistants. The object of these commercials is presumably to convince non-users, amounting to slightly over half of Americans, of the myriad ways in which the peppy, by-default female-voiced Google Assistant, Alexa, and Siri might each make modern living a little less anarchic, and a little less stressful.

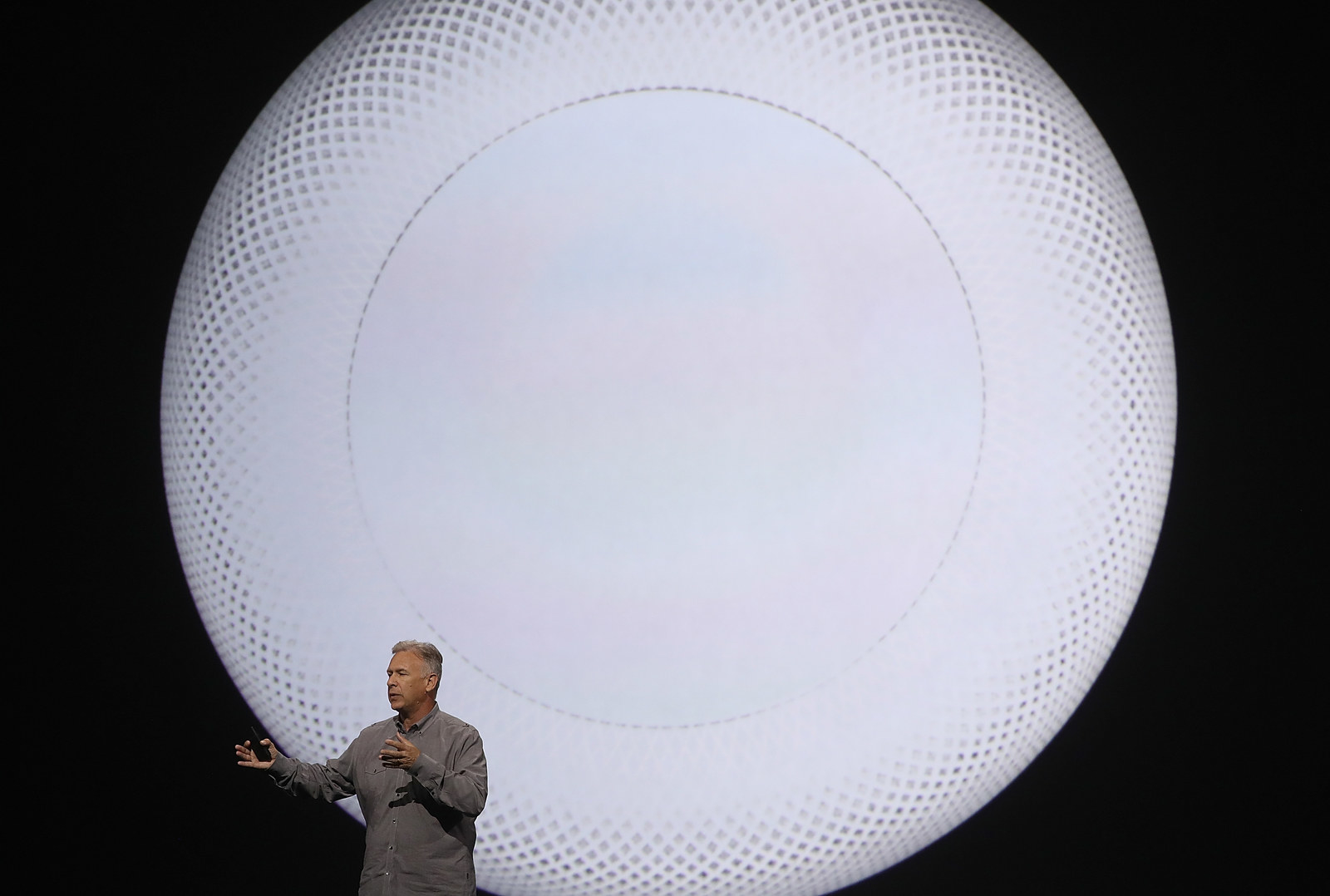

I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”

Small children are particularly useful for bringing the strangeness of this dynamic into sharp relief. Friends have told me numerous anecdotes about their very young daughters, sons, nieces, or nephews who carry on earnest conversations with Alexa or engage Siri in Beckettian dialogue. (In fact, the Google Assistant is getting a Pretty Please feature in hopes of teaching kids to be polite, while Amazon’s Echo Dot Kids Edition rewards kids for saying “please” with an easter egg built into the product.) In the telling of these stories, my friends are more bewildered by the technological turn of events in their households than the children themselves, who are usually unfazed. As adults, we tend to attribute these alien yet naturalistic interactions to the naivete of children, rather than to the inherently bizarre nature of relations between computers and people.

In their seminal 1994 paper, Computers Are Social Actors, Stanford researchers Clifford Nass, Jonathan Steuer, and Ellen R. Tauber capture the contradiction that underlies our dynamic with conversational computers: It is a paradox, in which we as human users “exhibit behaviors and make attributions toward computers that are nonsensical when applied to computers but appropriate when directed at other humans.” But we, as human users, are generally aware of the fact that computers are not sentient beings. What causes us to express social behaviors toward machines, according to robotics researcher Leila Takayama, is not the “absolute status of an entity’s agency,” but our perceptions of its agency. “As objects become increasingly endowed with computational ‘smarts,’” Takayama writes, “they become increasingly perceived in-the-moment as agents in their own right.”

Whether or not computers can have agency is arguably the root of our dystopian fears about voice AI. Kubrick’s HAL is terrifying not only because it personifies our fear of surveillance (HAL spies on its two astronaut minders by reading their lips) and our fear of clinical, non-negotiable logic that is incompatible with our humanity; HAL is terrifying because of the way that Kubrick and his collaborator, the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, wrote its capabilities and its conversations with the astronauts Dave and Frank — we perceive HAL to have personal agency, and a sense of self-preservation so fiercely human that it uses its omniscience and logic to commit cold-blooded murder.I’m admittedly part of this demographic of non-users — too self-conscious to issue commands at my phone in public, too cheap to splurge on a device that will listen attentively to my requests in the physical privacy of my living room. And yet, I don’t exactly fit the typical profile of a technological laggard: I worked for Google for many years on its web browser and cloud-based operating system; I’m the kind of house guest who peppers my friends’ Amazon Echos, Google Homes, and Apple HomePods with syntactically crafty questions. My personal passions and ambivalences about voice AI are probably not widely shared by the demographic that these ads are likely targeted toward: the 61% of holdouts who told Pew Research Center last May that they don’t use a voice assistant because they’re simply not interested.

For the tech companies invested in the long game of getting all of us to embrace conversational AI, consumer apathy may only be a near-term challenge. In the long run, the techno-utopian vision that these companies have crafted for voice AI — one that revolves around machines that will help us become our better selves — must counteract a legacy of pop culture narratives populated by evil, or chillingly value-neutral, computers, in addition to broader societal misgivings about AI. (Already scientists, entrepreneurs, and think tanks have begun to worry about the use of AI in autonomous weaponry and its Strangelovian potential for precipitating nuclear war.) While HAL was just one of the many plot elements previewed in the original 1968 trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey, in 2018 it is, tellingly, the thrust of the newly recut trailer for the rerelease. To begin rewriting the dystopian script of voice AI’s emergence in ordinary consumers’ everyday lives, its products and advertising oeuvre must negotiate the slippery terrain between the performance of human-like conversation and human-like agency, and make a case for voice AI amid growing unease about how it may forever alter our relationships with other people.

The idea of the conversational computer has made a home in popular imagination for so long that it does not occur to us how peculiar it is to talk to machines in the ways that we now do. Once, on a Lyft ride from the airport through rush-hour traffic, my driver — a friendly thirtysomething who flipped the driver-side sun visor down to reveal a photo of his 9-month-old twins — argued with the female navigation voice on Google Maps for the length of time it took to traverse several intersections. When the voice reminded him to turn right at the next red light as he eased to a stop behind several cars, he retorted, “Yes, lady, I know.”